MoBay Mobility: Navigating Transport on a Caribbean Island by Dami Adebayo (10 Nov 2023)

Last month, I was lucky enough to escape the UK and extend my summer with a trip out to Jamaica. Best known for its beautiful beaches & resorts, jerk dishes, rum and of course Bob Marley - I’m sure it's not a nation that you’d expect to end up on a Scottish Rural & Islands transport blog but alas…here we are.

Whenever I travel I’ve made a personal habit of throwing myself into the deep end of local public transport and refusing to rent a car, much to the frustration of whoever I travel with. So far it’s led to countless unforgettable experiences (for better and for worse!). And so I headed to Montego Bay determined to try whatever transport the city had to offer and to document it for the SRITC community.

Within 24 hours of touching down, I’d learned the three most important things about getting around MoBay (as the locals call it) without a car: (i) be prepared to wait (ii) be prepared to haggle and (iii) in some cases, be prepared to squeeze. Let me explain.

With roughly 80k local residents, transport infrastructure in and around the city is limited to say the least - especially when it comes to roads, rail and buses. The roads are narrow and winding, so traffic is inevitable. Pavements are sporadic (or nonexistent in some areas), so it's not a very walkable environment unless you’re comfortable sharing the street with cars. The last rail service to serve Montego Bay was back in October 1992. And to top it all off, there’s no formal bus system and the ‘bus stop’ is wherever you want it to be.

Despite all this, there is still a smorgasbord of transport options. While there’s no formal bus system within the system, they seem to have every type of taxi you could imagine.

First there are the ‘Route Taxis’. These are informal shared taxis that operate on fixed routes. At first glance it seemed any car could be a route taxi, but the easiest way to recognize them is by their distinctive red licence plates and single chequered stripe along one side of the vehicle. Costing around 80p per trip (regardless of length), these are by far the most affordable and authentic Jamaican way to get around. Naturally, this became my preferred mode of transport. You simply hail them along the main roads and tell them where you’re going: they then either drive off without you if it's not on their route, or invite you to take a seat (even if you can’t see any free seats). More often than not, route taxis are 7-seater vehicles that are filled to the brim with people. Very kind people, who will somehow conjure up extra space to allow you to join the ride. If you value your personal space, this probably isn’t the best option for you. If you want to meet locals, it's quite easy when you’re basically sitting on their lap.

Then you have ‘Tourist Taxis’. Tourist taxis also just look like normal cars, but they have white licence plates with red lettering. They’ll take you door-to-door rather than along a fixed route, and are a lot more comfortable (mostly just because they’re not shared with others). I unintentionally took a tourist taxi once, and the driver immediately made sure to clarify that he was the right taxi for ‘tourists like me’ and hastily reminded me he was going to charge me the equivalent of £10 (even though I could’ve done the same trip on a route taxi for 80p). That was my first and last tourist taxi.

There are also ‘Private Taxis’ which are pre-booked only and won’t stop when hailed. These prove to be best if you ever need to be somewhere on time (though the traffic may have another plan for you!). They are typically larger minibus vehicles and so a quick 5 minute trip can set you back the equivalent of £20. Private taxis are especially handy if you want to have a personal driver for longer day trips & excursions. In these cases, always make sure to agree to a fee in advance, but prices quoted typically start around £120 (not including tips).

Finally, there’s the adventure-seeker’s choice of hitchhiking. Now this isn’t something I would typically do, nor was it an option I intentionally took. Much like when we accidentally hailed a tourist taxi, we’d been standing out on the side of the road for over 25 minutes before a car finally stopped. I’ll blame the blazing heat for leading us to just hop in without asking too many questions. The driver was friendly and he was accompanied by a friend. It was only at the end of the trip when we asked him how much to pay and he took an awkward eternity to come up with a price, that we realised this probably wasn’t his typical day of business. Low and behold, when we left the vehicle we noticed a white licence plate with black lettering… should have been obvious!

That’s all to say, travelling around Montego Bay is truly an adventure. If you don’t choose to rent a car, you’ll have to decide on your preferred mode of taxi ranging from £0.80-£20 for a short trip. Note that there’s no sophisticated digital solutions paired with these taxis - you’ll either have to street hail until you find a taxi going in your direction or call multiple numbers till you find an available driver. Apparently some areas even offer motorcycle taxis and bicycle-driven rickshaws, but I sadly didn’t come across these. I can’t actually recall seeing a normal bicycle being used anywhere (likely due to the hilly, narrow roads which explains the transport mix being so car-dominated).

For me, the lasting memory of transport in MoBay will be that of the Route Taxis. They are a fantastic way to immerse yourself in the local culture, but certainly not for the faint hearted! I was surprised to see the use of regular saloon and MPV vehicles on fixed routes, but it makes me wonder whether the UK could take some inspiration from this as a community-organised solution for rural towns suffering from bus service cuts? Current regulations around vehicle sizes & licences for British transport services would make that tricky to implement in practice, but perhaps those regulations are worth reconsidering given the incredibly low costs per passenger which can be achieved with this sort of model.

Have Your Cake and Eat It: MaaS Story Part One by Jenny Milne (29 Sept 2023)

Every individual or family has their own daily routine whether that involves the school run, the commute for work, visiting friends or family or shopping. How this routine is achieved will depend upon where the individual or family not only resides but factors including but not limited to income, availability of transport options but ultimately there is an element, large or small, of choice.

The car is often the preferred mode in many areas as that choice can offer flexibility but not everyone can afford a car or indeed has a licence. Words that are unique to the transport sector to describe these phenomena include travel behaviour, trip chains or tours and there are many articles and journal papers exploring these concepts.

However, one critical factor that transport planners and policy makers have little control over is the role of the weather in the UK on travel behaviour or trip chains. Weather is such an emotive issue for the British population so what impact could this have on the adoption of more integrated transport services as proposed by the concept of Mobility as a Service (MaaS).

MaaS is a complex term with no harmonised meaning but for now, imagine and visualise a Victoria sponge cake. There are many different ingredients for MaaS, but for now, the focus is on the finished product which has two sponge layers with the jam in between.

MaaS is very similar in that one layer involves the integration of transport modes such as train, bike, bus and car whilst the top layer provides additional personalised tailored services. Within the cake, the jam in the middle represents the user as they use the transport services, while the top layer uses clever data analysis tools from layer one to offer a customised journey and tailor offerings/services to the user.

The services offered will be based upon the personalised data gathered in layer one of the cake when choosing the mode of transport. This additionality to the user is seen as ‘the icing on the cake’ by transport operators and policy makers, assuming that the user wants these additional services!

Sticking with the Victoria Sponge analogy, assuming the public is happy to cut a slice and have a piece of cake each day when undertaking their daily routine of travel, what happens when an unexpected factor such as the weather intervenes (In 2020, the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic could be described as an unexpected factor, however for the purposes of this article we are looking at, normal unexpected factors. COVID-19 was sprung upon society whereas the weather is constant).

Disruption, delay, fear, uncertainty or all concerns for the travellers. For example, can I ride my ebike on ice, is my childs school bus operating, how will I get to work, how long will my trip take, will the bus/train be operating. All these are natural and instinctive reactions on a day when the weather intervenes.

The original choices in the mode of transport are often a sub and conscious decision in that in the UK the use of an e-bike in snow or ice is deemed very challenging even with the correct tyres, however in Finland, cycling in such conditions is normal and something I’ve witnessed. Herein lies a cultural factor which inherently affects the unexpected intervention in the UK.

With this in mind, the role that MaaS in the UK can play when weather interferes will be different to other countries. As yet the role of unexpected interventions, such as weather, to a user’s daily routine has yet to be fully explored and addressed by those implementing MaaS solutions and technology.

For MaaS to be a dependable and desirable solution to the user (the jam), the unexpected interventions aren't the ‘icing on the cake’ but a core ingredient without which the cake won’t rise, and when baked, the slices won’t be eaten (user uptake is short lived), and ultimately the cake will be left untouched (MaaS will be a term assigned to history).

A successful Victoria sponge does require many ingredients but like the jam, the user lies at the heart. Without full consideration of all factors (ingredients) in the user journey/routine, we won’t be eating a nice Victoria sponge cake.

SRITC Gathering Transport Write-up by Matthew Kendrick (14 Jun 2023)

Hosting a conference is challenging; the challenges are compounded when you host a rural conference across three days at three different venues and have around 100 attendees signed up in person and around another 44 online.

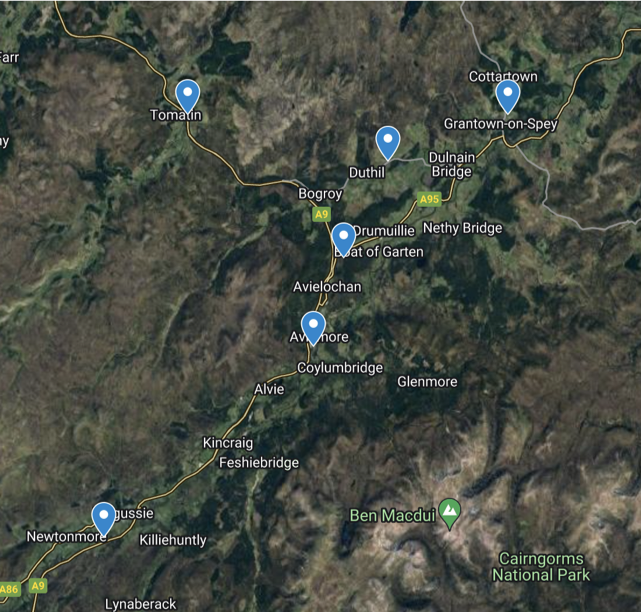

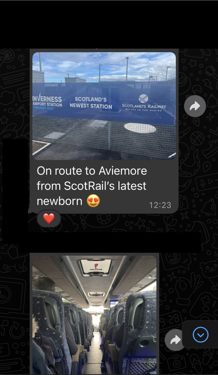

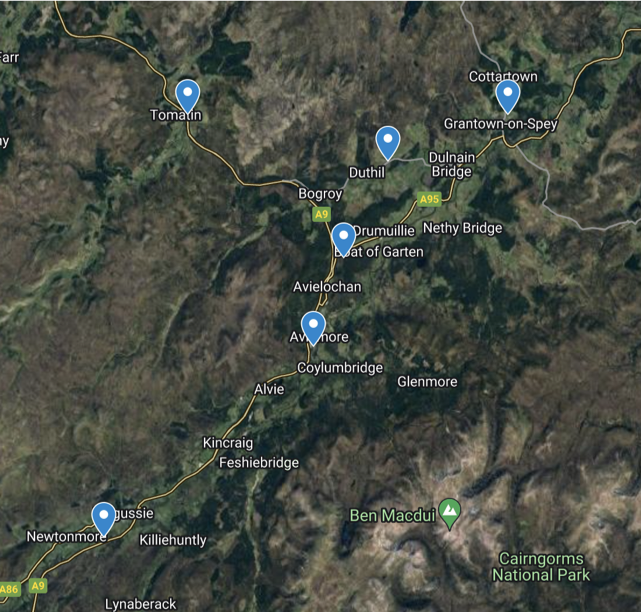

From 10th to 11th May 2023, SRITC hosted a transportation conference in the Aviemore area of the Highlands and Scotland. The conference aimed to unite the voices in rural transportation to network and discuss solutions to global transportation challenges from a rural perspective.

The event brought together the private sector, public sector and third sector. Attendees came in person from across Europe, including Sweden and Finland. Online, the conference's footprint expanded even further, with attendees from America and Japan in attendance.

One of the challenges faced by our team in pulling off the conference was the logistics of moving people around the venues and to/from the accommodation.

To meet the logistic needs of the attendees, one of our sponsors, Stagecoach, provided an electric bus and driver (Michael) to provide pick up and drop off attendees.

Before the conference, we compiled a list of people’s transport needs and created a bus timetable. We complemented the schedule with carsharing. There were also attendees who brought bikes to ride from their accommodations to the conference.

During the conference, we created a WhatsApp group for the attendees. Michael shared the bus’s location throughout the day and attendees shared photos of their journeys around the area.

As people started making the journey to the conference, attendees shared their travel experiences through photos and messages in the group chat. We learnt of one attendees’ terrible luck of missing three train connects that extended his train journey across Europe to 30 hours.

Through the WhatsApp group and shared transport options, attendees were able to organically connect with each other and break the ice. The challenge of transporting people rurally turned into a fun feature of the event.

A few learnings from the SRITC Gathering of 2023 by Magnus Fredricson (31 May 2023)

One of several pleasant experiences during the gathering was a little walk from the community centre in Boat of Garten to the newly built pump track in the nearby forest.

Who built this? Asked I, as I observed the sign with instructions for use and safety regulations. This question, as it is, encapsulates a large difference between Sweden and Scotland. In Sweden the answer would invariably have been: the municipality. Or at least: the municipality paid for it.

In Scotland the third sector plays an entirely different role in society and social enterprise is a thing. Third sector actors take on professionalised roles and are expected to deliver professional services.

The SRITC itself is a social enterprise, run by a PhD candidate with a professional advisory board of which I am fortunate enough to be a part. Still several start-ups with large investments or social enterprises with research directors were a part of the gathering. This signals another societal contract.

The gathering was opened by a speech from the transport minister of the Scottish government. There are structures in place where social enterprises both influence policy and deliver insights as well as produce services.

One might, and rightly so, argue that these roles of the third sector are a must in a society where the public sector is retreating. This, however, would be an overly simplified understanding of the situation.

Public cooperation with third sector goes back a long time in Scotland, and the government has actively supported the emerging of a third sector through different initiatives such as SensScot, Social Enterprise Network Scotland, a social enterprise umbrella organisation which focuses on supporting social entrepreneurs in all walks of life in business, in government and in particular, creating social enterprises.

In fact, one of the participating social enterprises also illustrate the differences in the societal contract: Collaborative Mobility UK. They are a charity dedicated to the social, economic and environmental benefits of shared transport.

Their webpage outlines their mission: We work collaboratively with national, regional, transport and local authorities as well as the private sector to further these social, economic and environmental benefits. We do this via accreditation, research, policy, guidance, engagement and advocacy. The research presented by them is also useful in the Swedish context, where for instance the report on Digital Demand Responsive Transport issued in March 2023 has several recommendations suited also for Sweden.

In Sweden public transportation is run by regional authorities. They typically procure the actual production of transport and all of their resources are located there. Little or no room exist for local collaborations with social enterprises, if they would even exist.

One possible solution in a scarcer geography would be a “village bus” as infrastructure provided by the regional authority instead of a regular bus that serves the village maybe once per day. Driving would be the responsibility of the local community.

These types of solutions are not in place in Sweden, where the public sector in practice monopolise resources and production of mobility services as well as other services, e. g. health care, education and others. (There are private actors within the education sector, some are even co-opted.) Sharing resources and indeed power is not common for the public sector of Sweden.

SRITC, Scottish Rural and Islands Transport Community, addresses transportation in scarcer geographies. There are large similarities between Swedish and Scottish geographies. Scarcity or “un-density” is abundant. In a neoliberal, “market driven”, system for public transportation scarcity of customers will not attract solutions or services.

Bus services in rural areas are deemed “non-profitable” and shut down. Exactly what non-profitable means in a publicly funded operation is not clear. In Sweden the average funding of public transportation amounts to 50% tax and 50% ticket sales.

An economization of public transportation, for instance through procuring the actual services from private, profit driven companies, brings the risk of reducing citizens to customers, and paves the way to understanding a bus line as non-profitable.

Almost all municipalities in western Sweden will cite “accessibility” or public transport as a challenge, particularly in rural – non dense – geographies. Obviously, un-density drives cost for public transport for instance per person-kilometre.

Participants in the gathering also included representatives from national parks and other attractions. Mobility is seen as an integrated part of developing tourism or local communities, this realisation is obvious also in a Swedish context, at least among municipalities and other local actors.

The policy controlling public transportation in west Sweden does not include these perspectives at all, often times creating quite the tension between local and regional levels. It appears, at least from the perspective of a visitor, that dialogue and co-creation between different actors in different geographical scale is more fruitful, and that well-trodden paths for it exists based in the tradition outlined above.

Also, pilot-testing is an abundant modus operandi in Sweden. There is much less talk of that in Scotland. Testing, learning and continuous development are obviously key to enable sustainable mobility in scarcer geographies, but pilot-testing, sandboxing, tends to limit impact of learnings created within regular operations. A mindset based less in pilots and more in continuous testing and learning would probably be more fruitful.

Digitalisation is key, where cell phone coverage is a prerequisite for dynamic mobility. Cell phone coverage is better in Sweden. Several start-ups and more established companies supply different kind of technical platforms with different levels of integration. Standardisation, in a wide sense, is needed but the market is still immature.

Also, business models for whole eco systems of services and platforms need to be developed. Actually, the need is sustainable income models where, in Sweden, regional authorities need to play a part.

Tentative recommendations for the Swedish context would include openness toward innovation and co-creation of solution for accessibility needs in scarcer geographies. These processes, rather than pilot-projects, will need to enable a more flexible use of public resources rather than solely reserving resources for existing structures and solutions.

The market will not produce solutions in scarcer geographies, and no viable business models will be found that facilitates mobility services where customers are fewer. Budget will have to be allocated from public financing to enable solutions for better sustainable accessibility.